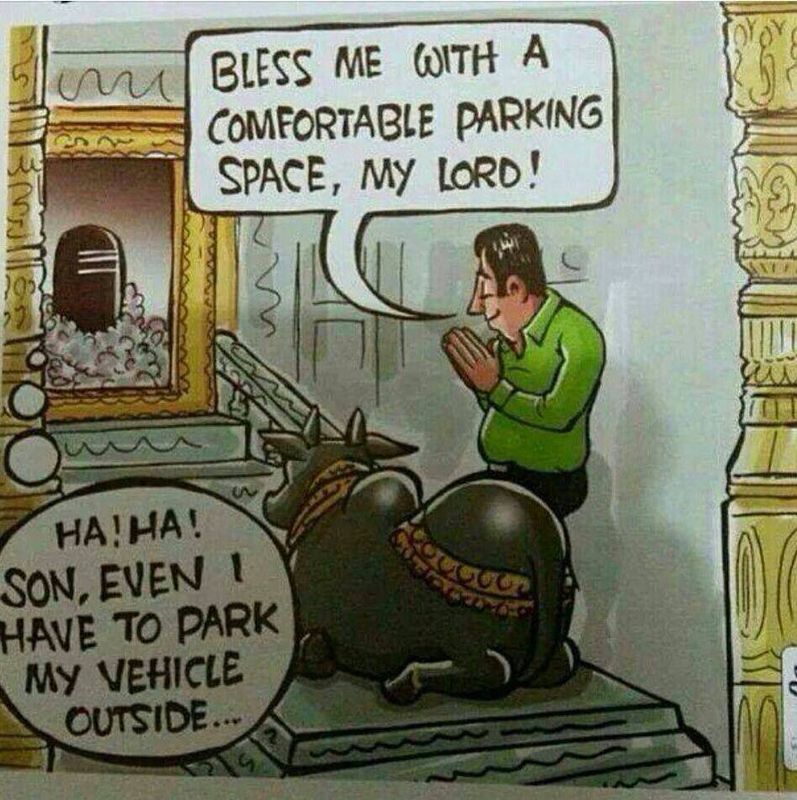

Prayers for Parking Space……Lol !

July 22, 2014

Source- Unknown

A sip of joy-Yum Cha !

December 6, 2013

By Susmita Saha

Photograph by Jagan Negi

Enjoy an array of specialty tea and lipsmacking dimsums to go along, at the Yum Cha Festival, at The Claridges in Delhi

A sip of joy

Sure it’s a tea, but it’s one that may put champagne to shame. It’s priced over Rs 1 lakh per kilo and goes by the name of Da Hong Pao. To take a sip of this prized concoction, head to The Claridges in Delhi where the Yum Cha (tea drinking ceremony) Festival has been on since November 7. One of the few dedicated tea and dimsum festivals in Delhi, Yum Cha offers more than 11 varieties of the beverage, including Lapsang Souchong, Long Jin, Houjicha, Yunnan Red and Bai Mudan. A mix of white, oolong and black, the hotel’s tea inventory also boasts varieties that are therapeutic, floral or fruit flavoured and intensely fragrant. For instance, the Yunnan Red Tea or Dian Hong is often fermented with fruits like lychee and longan and releases golden-orange liquor when brewed.

Yum Cha teams these delicate brews with Cantonese small eats that straddle different food groups like pork, poultry, beef, seafood and vegetables. Mild-flavoured teas like Long Jin are ideally paired with dishes like steamed scallop and asparagus dumplings or mini prawn chang fen (prawn filling in long intestine-shaped casing). Says executive chef Neeraj Tyagi, “Indians are now taking to tea (the no milk-no sugar avatar) in a big way owing to its health benefits. So we decided to host Yum Cha to give Delhiites the best mix of tea and dumplings.”

Source- http://www.telegraphindia.com

Humans more absorbed with Mobile than other humans

September 3, 2013

The Economist explains Why don’t Americans ride trains?

September 2, 2013

by N.B. | WASHINGTON, DC

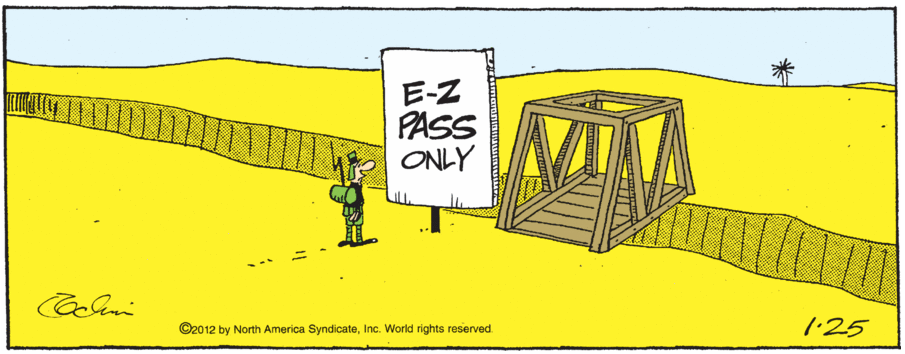

AMERICA has by far the largest rail network in the world, with more than twice as much track as China. But it lags far behind other first-world countries in ridership. Instead of passengers, most of America’s massive rail network is used to carry freight. Why don’t Americans ride trains?

Rail ridership is usually measured in passenger-kilometres—one passenger-kilometre represents one passenger travelling one kilometre. One 1,000-person train travelling 1,000 kilometres would on its own account for a million passenger-kilometres. Yet American railroads accounted for just 17.2 billion passenger-kilometres in 2010, according to Amtrak, America’s government-backed passenger rail corporation. In the European Union, railways accounted for nearly 400 billion, according to International Union of Railways data. When you adjust for population, the disparity is even more shocking: per capita, the Japanese, the Swiss, the French, the Danes, the Russians, the Austrians, the Ukrainians, the Belarussians and the Belgians all accounted for more than 1,000 passenger-kilometres by rail in 2011; Americans accounted for 80. Amtrak carries 31m passengers per year. Mozambique’s railways carried 108m passengers in 2011.

There are many reasons why Americans don’t ride the rails as often as their European cousins. Most obviously, America is bigger than most European countries. Outside the northeast corridor, the central Texas megalopolis, California and the eastern Midwest, density is sometimes too low to support intercity train travel. Underinvestment, and a preference for shiny new visions over boring upgrades, has not helped. Most American passenger trains travel on tracks that are owned by freight companies. That means most trains have to defer to freight services, leading to lengthy delays that scare off passengers who want to arrive on time. Domestic air travel in America is widely available, relatively cheap and popular. Airlines fear competition from high-speed rail and lobby against it. Travelling by cars is also popular. Petrol is cheaper than in Europe (mostly because of much lower taxes). Road travel is massively subsidised in the sense that the negative externalities of travelling by car, including the release of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases, are not fully offset, and most major highways—which cost tens of billions to maintain—are still free of tolls. And finally, Barack Obama’s embrace of high-speed rail has heightened a political battle over rail that doesn’t exist quite in the same way in other countries (although the fraught debate over high-speed rail in Britain comes close). Opposition to rail is now often seen as essentially conservative, and Republican governors oppose rail projects to boost their conservative image.

America’s national-level politics are unlikely to become more functional in the near term. So all this leads to an inevitable conclusion: what happens with California’s planned high-speed rail system matters a lot. If it is completed, works and is popular—all of which are uncertain—other states will undoubtedly take note. If California’s high-speed dream fails, it may be a long time before America has true high-speed service. And by that point, America may be ready to put in a call to Elon Musk. Hyperloop, here we come!

Source- http://www.economist.com

India’s remote north-east The road to Tawang

September 2, 2013

by A.R. | TAWANG

DRIVE from the Brahmaputra river, in the plains of north-eastern India, and towards the Himalayas to the north, and hefty obstacles lie in your path. The road up to Tawang, a Buddhist monastery-town near the border with China, takes two long days of travel. From the start you traverse a narrow and muddy track, often single-lane and scattered with rocks. Along this way plod army lorries, petrol tankers, jeeps crammed with passengers. Teams of labourers toil by the thousand along the length of the road. Some chip at stones, others lug rocks aside from the slow-moving traffic.

In time—supposedly another five years—this broken, narrow and vulnerable road will be upgraded to become a “national highway”. But even tarred and smooth, it will offer hazards aplenty. Heavy fog rolls in as the road climbs higher: shortly after a sign gives warning that you are entering a fog zone, the mist closes in and rain begins to patter. With visibility at just a few metres, and with the sound of a huge river rushing in the steep valley below, progress is reduced to a crawl.

There are excuses for the poor condition of the road. A century ago this territory—a stretch of remote land parallel to Bhutan and stretching up to the borders of Tibet—was hardly considered a part of India. The British, before a treaty in 1914 in Shimla, had broadly decided to leave the hill tribes of land now called Arunachal Pradesh to themselves. Tawang, and its surroundings, were administered only loosely, by Buddhist monks from Tibet who levied taxes but did not bring modern government, let alone build infrastructure such as decent roads.

The terrain, too, is hard going. The farther up the road you move, the more unstable the land becomes. Rockslides and landslips are common. Waterfalls thunder from the valley sides. When the rains are strong, these carve new cuts and ravines into the hillside. Much of the valley at lower altitudes is thickly jungled, but higher up trees have been stripped away, encouraging erosion. Heavy monsoon rains bring annual havoc. So steep are the valley edges that the road has to wind back and forth on itself, coiled snakelike up the sides of the mountain.

But there are rewards, too. The end of the first day of driving, past military camps and roadside villages, brings you to Bomdila, a monastery-town on a hillside. Next morning the evidence of Tibetan heritage is already clear: at the monastery, pristine in the morning sunshine, gardeners snip at grass with tiny shears and monks spin at prayer wheels. Soldiers from a nearby military camp walk to a dairy, clanking small, tin churns in their hands.

From here on there is also evidence of the valley’s most turbulent recent history: the invasion of 1962 by China’s army, which cascaded down from the Tibetan plateau high above. The war, 50 years ago, was the result in the short-term of Indian assertiveness, especially in the face of Chinese expansion farther to the west, in Kashmir. The mutual border was (and is) a disputed line drawn by colonial authorities with a thick nib, known as the McMahon line, after the Indian foreign secretary of 1914. China refused to recognise India’s sovereignty over the territory it drew in. Rather than assuage its northern neighbour, however, India chose to push soldiers—and frontier posts—farther and farther forward, even north of the McMahon border.

Yet the longer-term causes of the fighting were messier. China, in the 1950s, had quashed an uprising by Tibetans north of the border. It had also stolen into territory in Jammu and Kashmir state, which India’s considered to be its own land. In 1959 the Dalai Lama, Tibetans’ spiritual leader, fled into India, taking refuge at the monastery in Tawang. He was greeted warmly by India’s politicians and public. Many thousands of other Tibetans followed, forming a government in exile. Arguably the conflict of 1962 was in part a belated, vindictive, reaction by Mao to punish his neighbour for granting asylum to an internal opponent.

Signs of the war are mostly gone. But memorials exist, mostly Buddhist-inspired in their design. They bear plaques with lost lists of names of Indian soldiers (many of the fallen were Punjabi Sikhs, so long lines of “Singh” are carved into black marble) dot the roadside. At the locations of particularly fierce battles—which the Indians, without obvious exceptions, lost—the memorials include accounts of fierce rearguard fighting, in which heroic soldiers gave their lives so others could escape.

By the highest point of the journey, at Se-La pass, the wind is chilly and the air is thin. At 4,700 metres soldiers, road labourers, drivers and tourists alike feel the reduced oxygen. A Chinese-looking archway welcomes travellers to Tawang district, and from here on are views of snow-capped peaks and the Himalayas proper.

Tawang itself is breathtaking. Its white-walled monastery is strewn with colourful flags and banners. Autumn flowers, some wild, many in pots on houses, decorate the roadside. The people here have the look—high cheekbones, jet-black hair, round faces—of Tibetans, the more so as many are dressed in traditional red and purple clothes, some with yak-wool hats, as they gather to hear a visiting Buddhist leader at the monastery.

Yet it is impossible to forget the military presence. Helicopters lumber overhead with steady regularity—some moving to patrol the border with China, others delivering rations and materiel to forward bases, yet others bringing higher-ranking officers and dignitaries to work. Taking a morning walk I am accosted by a friendly man wearing the unmistakable uniform of a senior policeman the world over: an ill-fitting shiny suit and sunglasses. He quizzes me about my permit—all foreigners need a special pass to enter Arunachal Pradesh—and demands to know if I have yet registered at the local station.

For all that, Tawang is peopled by open, friendly and welcoming residents. By turns the elder ones tell stories of the war of 1962, of the sudden invasion, the panic among Indian forces, the burning of bridges and houses by the retreating army, the relative good behaviour of the invaders. Many interviews, conducted at the monastery, are done to the chime of spinning prayer wheels and the steady murmur of prayers being uttered.

That the border with China is no more firmly settled today than it was in 1962, or 1914, seems to worry only a few in Tawang. From the perspective of local people, the Indian army today looks far better equipped—far mightier—than ever before. Half a century ago the Assam Rifles and other frontier forces carried weapons dating from the first world war, and were dressed in thin cotton shirts suitable for the plains below, not the early winter of the Himalayas. They were easily swept aside by better-prepared Chinese rivals.

Today the army is growing fast. One China expert in Delhi describes half a million soldiers (both Chinese and Indian) camped along the sides of the McMahon line. India is raising four new divisions, some 70,000 additional soldiers in all, to be deployed in Arunachal Pradesh. India’s much expanded economy is providing huge resources for weapons, recruitment, and soldiers’ salaries, to fund its heavy army presence here.

Yet few have much conception of what lies over the border. On the Chinese side, in Tibet proper, the terrain is easier for a rival army. And being more skilled at building infrastructure, the Chinese now have both road and rail to supply their forces on the frontier. For now, nobody imagines that there could be a replay of the war of 1962 in Tawang. But if tensions were to flare again, it is a fair bet that, despite Indian gains in recent years, the forces from the north would be the better-equipped and prepared.

The drive back down from Tawang is no easier. It requires another two days, complete with delays as a bulldozer is dug out from a landslide. We wait too for an explosives expert to dynamite a huge, fallen rock. The route down is entertaining in its own way, punctuated with interviews of elderly politicians and monks, and another night at a monastery’s guesthouse. But the warmth of the Indian plains below is welcome.

Crazy Adventures

August 26, 2013

The Road Goes Ever On: Route 66 and the American Dream- A Blast from the past

June 17, 2013

ANDREAS FEININGER

One could search long and hard before finding a more stirring two-word phrase in the English language than “road trip!” It works with families, couples, old friends, new friends: pack two or more people into a car with some good music, high-sodium snacks and no fixed, unshakable destination, and you’ve got the ingredients for a (more often than not) excellent adventure. After all, the car — or motorcycle, or VW microbus — is far more than a mere utilitarian contrivance. For roughly the past 100 years, ever since Henry Ford began mass-producing his revolutionary Model T, Americans have been engaged in a love affair with automobiles and, in a much larger sense, with the enduring myth of the open road. Has there ever been a culture that extolled movement for the sake of movement as fervently as 20th century America? In movies (It Happened One Night, Easy Rider, The Straight Story, Lost in America and countless others) and, of course, in popular songs (by Woody Guthrie, Chuck Berry, Springsteen, Lucinda Williams, Dylan and the rest) the notion of getting behind the wheel and simply taking off is celebrated to the point where road-tripping feels like a universally embraced national religion. In 1947, Andreas Feininger made a photograph in Arizona that might be the single most perfect picture ever made of the single most famous road in America: Route 66, the 2,400-mile “Mother Road’ that runs from Chicago through Missouri, Kansas, Oklahoma, Texas, New Mexico, Arizona and finally across the Mojave to Los Angeles. The picture is a remarkable distillation of an idea: namely, that the American West is a place where people find themselves, or lose themselves, amid heat, sun, open spaces, enormous skies. Despite the fact that Feininger’s photograph is packed with “information” — cars, a bus, human figures, a gas station, a garage, towering clouds, an arrow-straight ribbon of road to the horizon — its essential emptiness can be read as a metaphor for the blank slate that innumerable people have sought in the West. Here is where you can redefine yourself, the scene suggests. Reimagine yourself. Reinvent yourself. Then keep moving. Like the American West itself — or like the mythical West of our collective memory — Feininger’s Route 66 feels both companionable and limitless. We want it to go on forever, and if only we have wheels, and enough time, and enough gas, deep down we believe it can. — Ben Cosgrove is the Editor of LIFE.com

Source: http://life.time.com

KOREAN FOOD !!

May 29, 2012

Do you live to eat or Eat to live !

Well I am certainly the former kind and not the latter. Life in the highway business takes us from different Dhaba on different highways in India to ones in trying different cuisines in different countries .

During one my recent travels to Korea I had the pleasure of enjoying the mouth watering Korean cuisine .

The Free Starters : With Every Korean meal you get some really healthy and yummy starters , and they replenish them as they finish . For the vegetarian friends , all the starters are veg!

Bulgogi : This is one the most delicious Korean dishes , it serves with a burner fitted on the table and eaten together with Korean Letuse leaves

A Typical Korea Spread : The milky stuff in the soup bowl is actually a local alcohol

Vegetarian Delights: A Special fermented Leave

A type of Kimchi

Another fermented Leave preparation

ALL IN ALL KOREAN FOOD TASTES GREAT.IT HAS A LOT OF LEAF DISHES….. YOU PROBABLY WONT FIND THIS ANYWHERE ELSE….

Funny Rides

April 24, 2012

[nggallery id=7]

Meditation

February 9, 2012

Lord Buddha was asked,

“What do you gain by Meditation ?”

He replied,” nothing,but let me tell you what I lost: Anger, Depression, Insecurity, Fear Of Old Age & Death”